It’s happened to everyone: you go back to a place that was once very important to you, and find that it has transformed somehow while you were away.

It is smaller, or run-down, or just underwhelming. And you feel pangs of nostalgia or disappointment — maybe mixed with a sensation of accomplishment or even wisdom, because you see that you have grown up, your perspective has widened. You’ve learned things in the years that have passed.

And hoping for this, sometimes — when I’m feeling especially strong, or defiant — I drive past places where especially bad things happened. And I can report that over time, and with practice, they have become more ordinary. The malevolent sparks that used to fly off of them have faded, and from the inside of my car they mostly just look like buildings, the way they probably do to everyone else.

(I haven’t stepped inside those particular places again. Years and maybe even decades have passed since the people I remember moved away, so maybe they wouldn’t feel like houses of horrors anymore. But even if someone were to invite me in (unlikely), I know I couldn’t go inside, and the force that would stop me from doing it feels just as strong as the force that stops me now from walking through their closed front doors.)

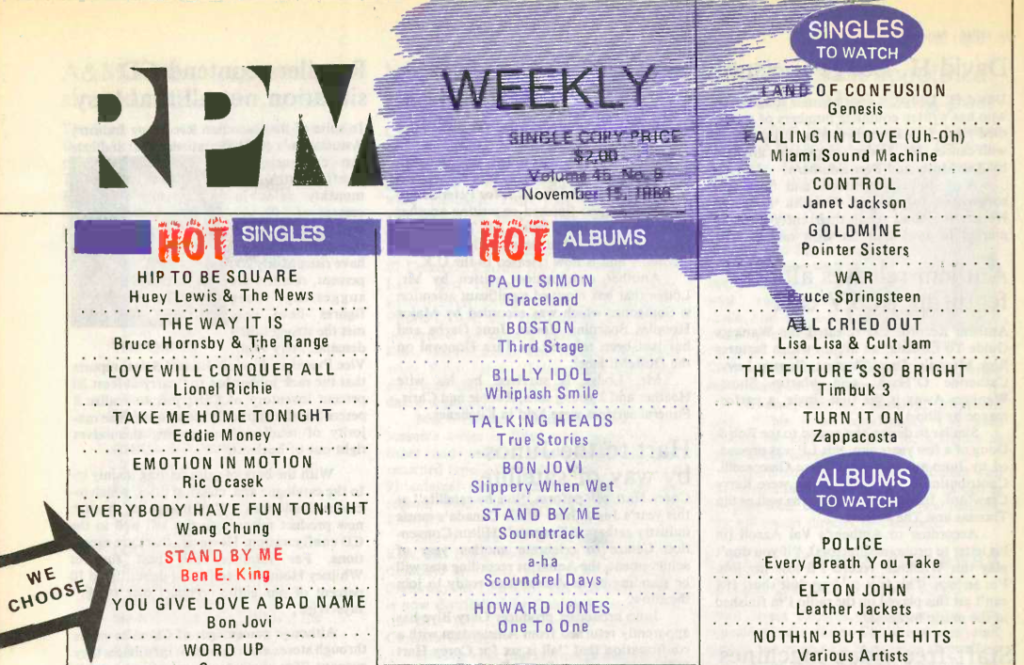

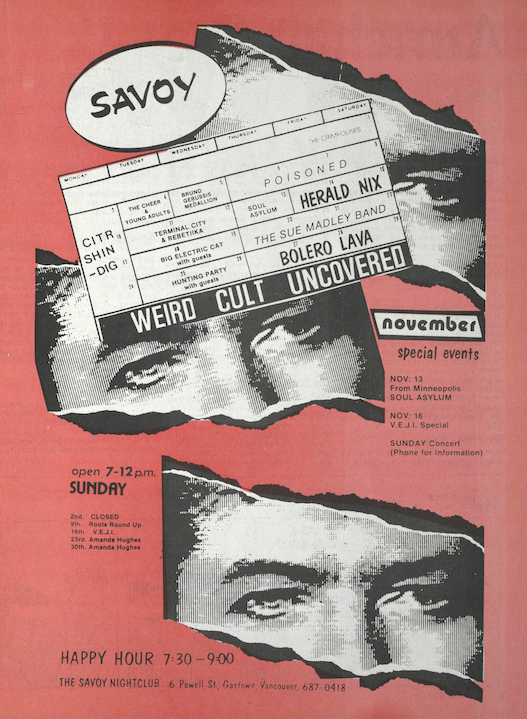

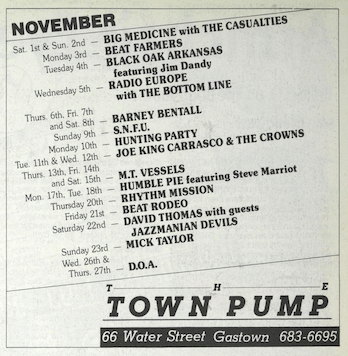

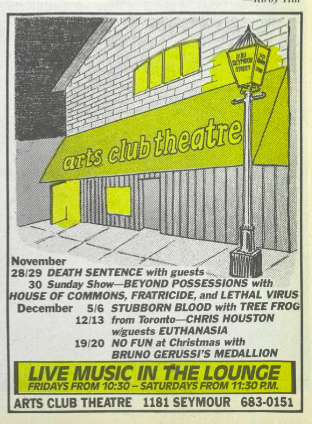

Less often, I go into a space where a nightclub or bar I knew used to be, places where I sang with my old bands (and watched many more). When that happens I always feel disoriented, and swivel my head around, trying to picture how it used to be. Where was the stage, anyway? Where did we put our gear? Who were the other bands we played with? There were so many hours, and so many details, and so many other people, and so much of it is completely lost to me — so now I sometimes find old posters or newspaper listings for shows I have no recollection at all of playing.

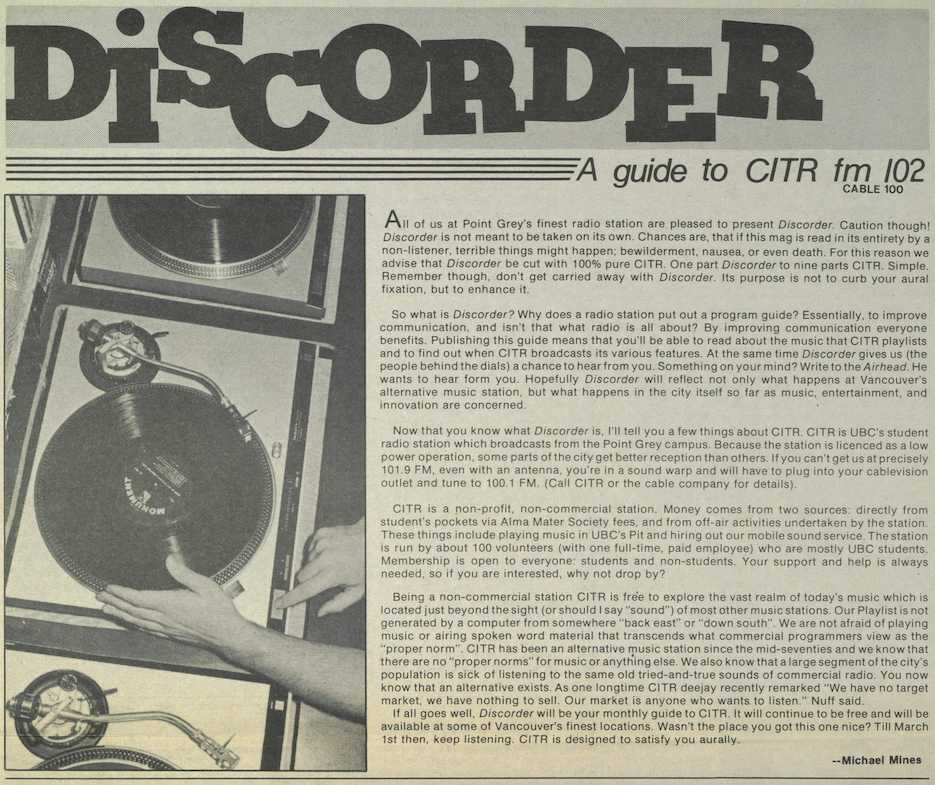

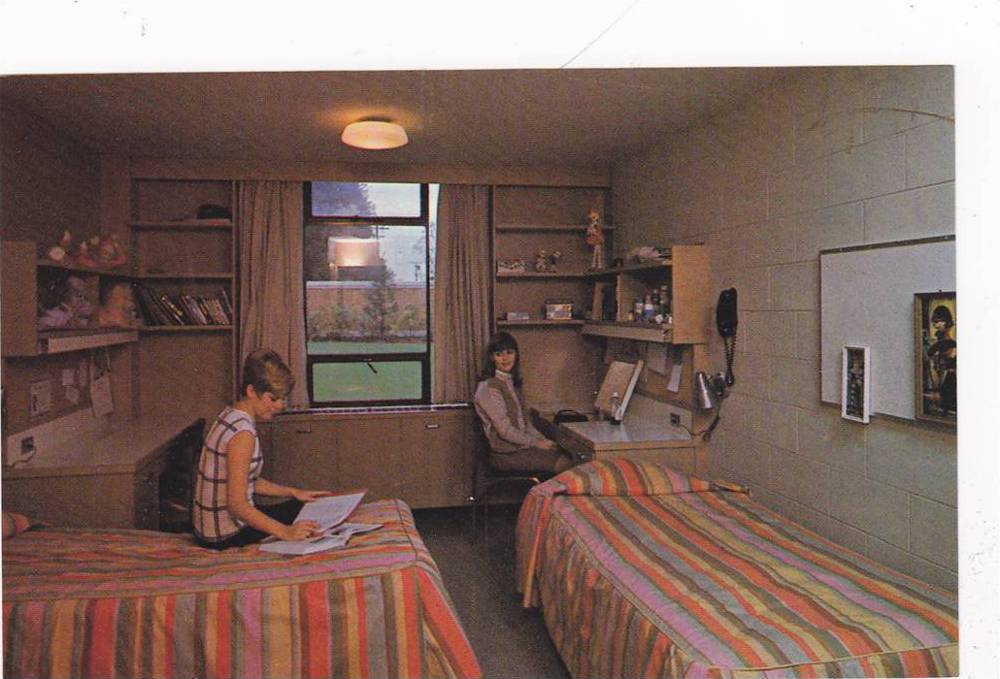

Which is what I was expecting a few days ago when I went back to the dorm where I lived from September through April in my first year of university.

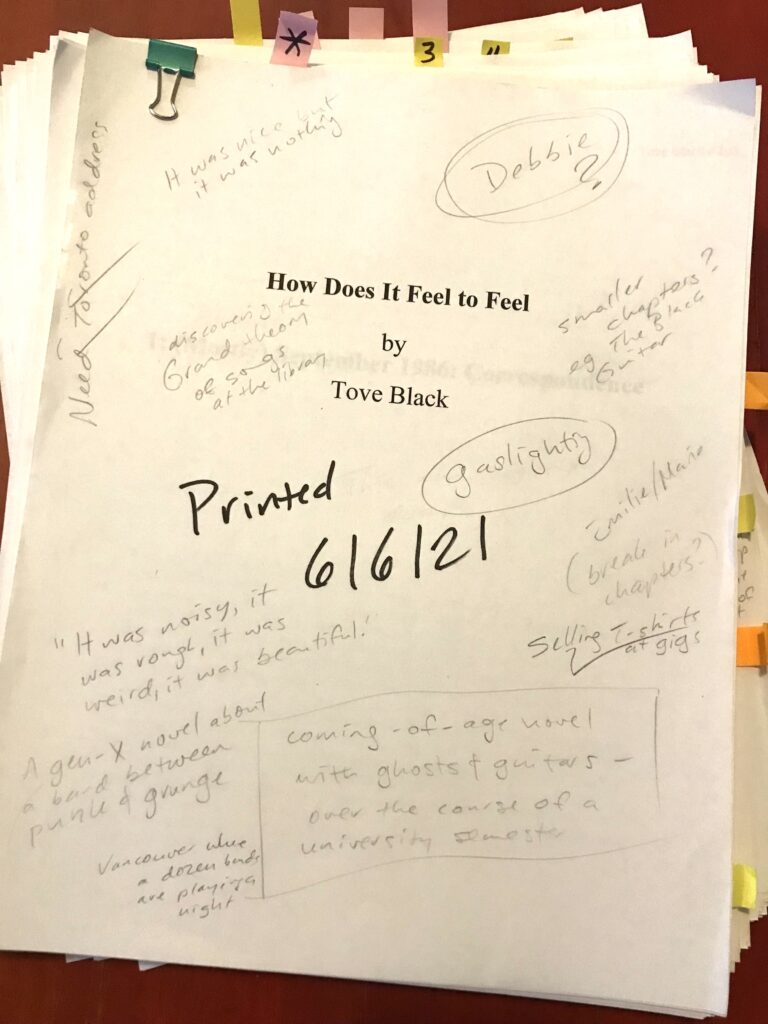

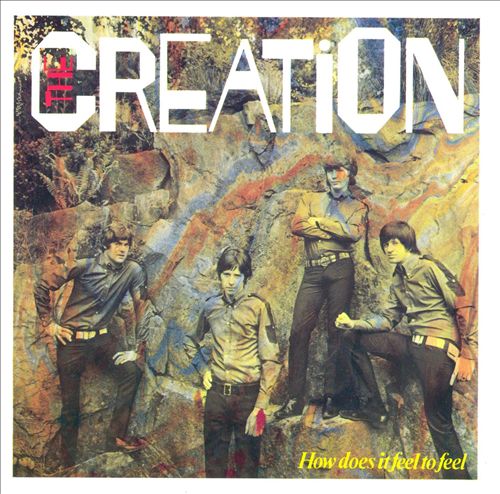

This dorm is the setting of a novel I’ve been working on for quite a while now (How Does It Feel to Feel — in what I hope are the polishing stages now), and in my own imagination it has become very real to me again, even after my long absence.

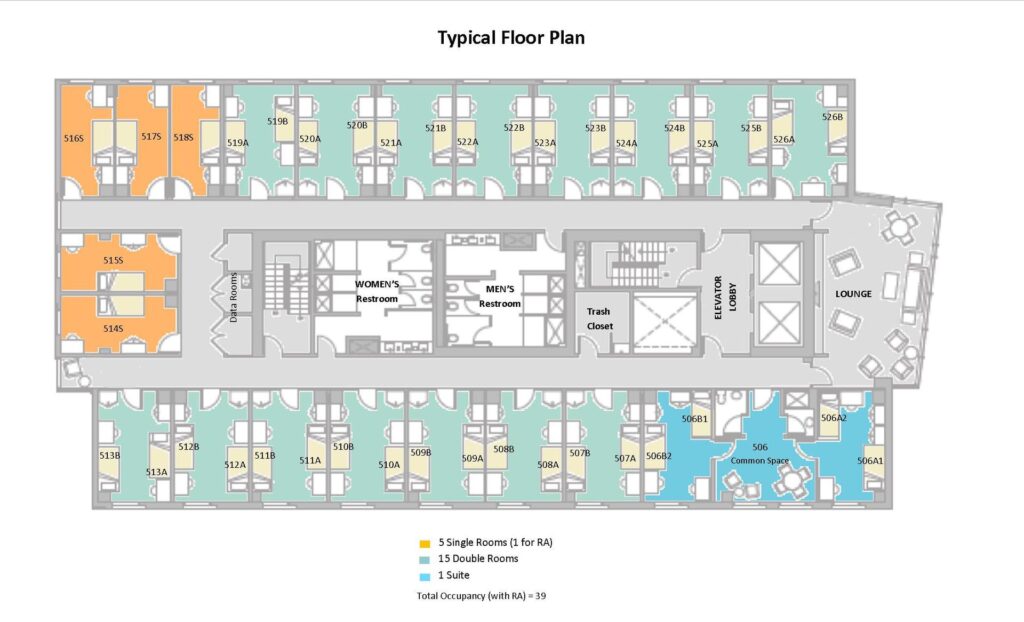

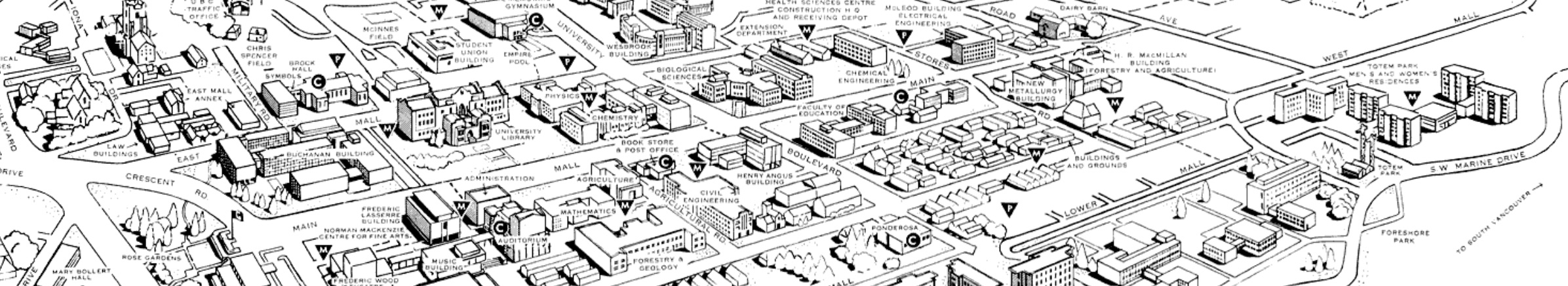

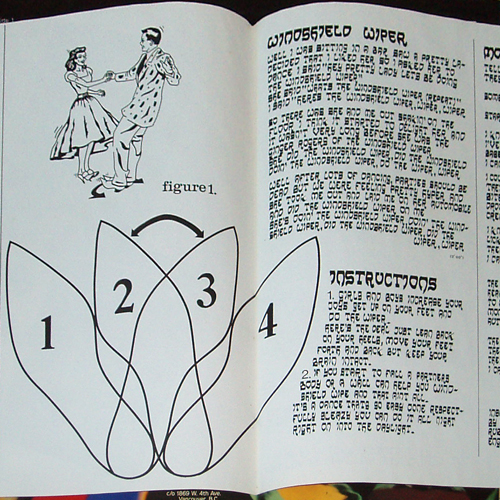

As I wrote, I could picture the layout of the floor very clearly, and how many rooms there were, and where the shared bathrooms were, and the stairways, and the elevator. I could even picture the walk to the dining hall, and the wall of mail slots, and — less distinctly — going past the common rooms on the main floor, spaces I probably only went into two or three times, for mixers — the kind of dance parties that happened in those institutional-looking spaces, soulless boxes even with the disco lights. (And thinking of that now, I am certain that they had worn parquet floors.)

And because I could picture it all so clearly, I assumed I was wrong. But when a kind student (the daughter of some friends) let me come up to her floor to look around last week, it turned out that I was right.

The stairway was the same. The H-shaped floor plan was the same. When I looked down the hallway the row of doors was almost identical to what I remembered. Although —as you’d expect — the old stained carpets have been replaced, and there is different paint.

And (of course!) there is no sign of the pay phones that were literally and metaphorically at the centre of the floor when I lived there.

I didn’t stay long, but it turned out that the spaces I remembered and thought about the least had changed the most. The dark common rooms on the main floor were opened up and bright. The dining hall, from outside at least, actually looked cheery — which is not the way I remember it.

Maybe the strangest part: it didn’t feel weird to be there again, even after more than thirty years, even though the place was so important to me as a young person, and is so important to this story I’m telling.