The Book of Love, by Kelly Link

I was nervous about starting The Book of Love. What if my expectations were too high for this novel? What if I didn’t love it? When her last book came out (White Cat, Black Dog), I was that person who pre-ordered a copy, ran to my local bookstore as soon as it arrived, and then took it to a local park to start reading it right away — because I couldn’t wait till I got home.

Because while this is Kelly Link’s first novel, it’s not her first book — she has published four short story collections and won a lot of major awards. So even if you’ve avoided reviews before picking up The Book of Love (as I did), you might already have read her work.

(And even if you haven’t read her short stories yet, you may have heard her compared to people like Shirley Jackson, Jorge Luis Borges, and Angela Carter.)

My own introduction to Link’s writing was “The Specialist’s Hat” — which I discovered after someone in a workshop said her name in that kind of hushed tone that writers use for their real heroes. And it felt world-changing to me when I first read it — it shook me in the same kind of way I remember being shaken when I saw the Blair Witch Project in a theatre back when it came out. Like that film, Kelly Link’s stories often upend the rules and drop you into a weird world that doesn’t make sense and yet feels believable, where surprising things happen quickly and without explanation, where you are left feeling unsteady and uncertain: what just happened?

That’s an overall effect thing that I don’t want to try to dissect. But one of the factors may be a craft decision that so often sticks with me from the stories — a sense that Link is intentionally leaving loose ends and unfinished elements — defying writing “rules” that require stories to be tidy and to hit certain marks.

So her style is subversive and bold. It’s thrilling. But that past experience also made me a little anxious about picking up this novel — because what if the rule-breaking didn’t work in a longer format?

Or worse still — what if The Book of Love didn’t break the rules at all?

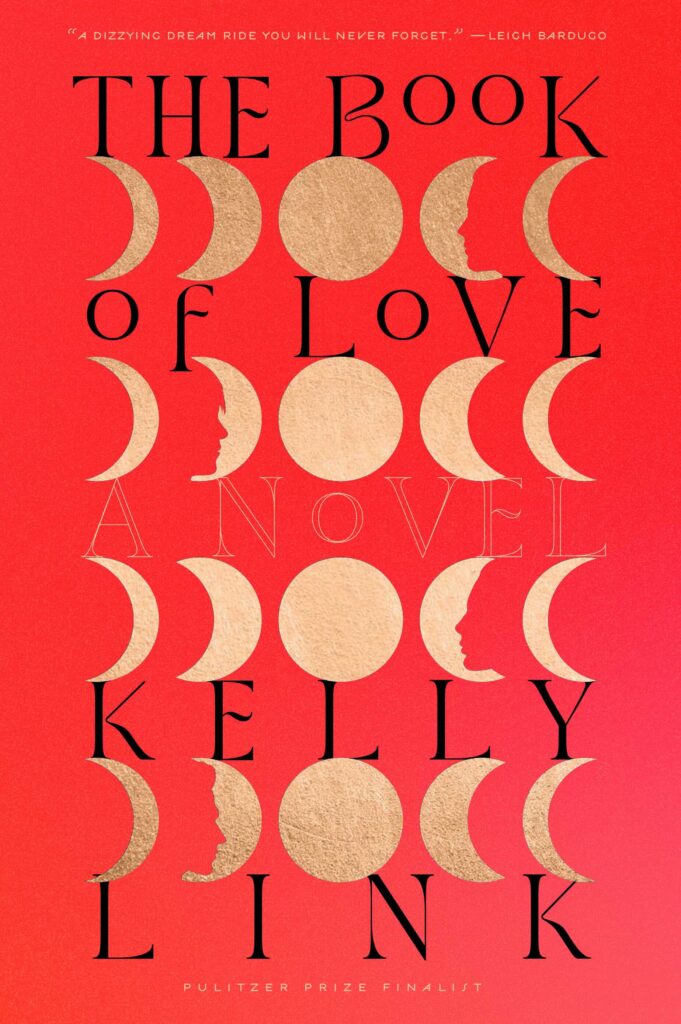

Four rows of images of moon phases, each row with a profile silhouetted in one of the waxing or waning moons — signalling that this will be a complex, layered story of multiple characters, and that there will be lots of changes.

Plus, of course, the moon symbolism.

And I am reporting back with good news. Very good news: The Book of Love does break a lot of the rules I hoped — especially the ones I’ve seen in well-known instructions to novelists, the types that would make the story predictable.

It also follows the rules that matter more (at least to me): the characters are treated with respect (and yes, love).

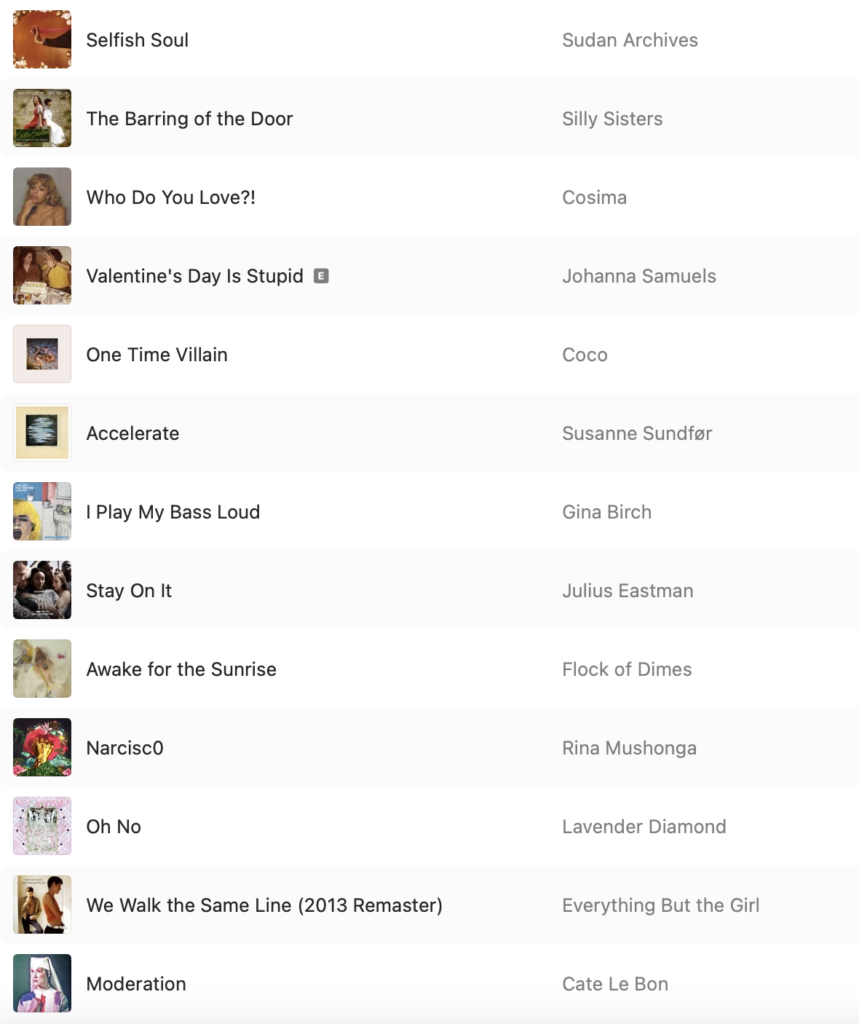

And where details matter, Link takes them seriously. As a former campus radio kid who used to play in bands, I can be pretty sensitive about music details (probably far too sensitive). Would a kid in X type of band really play Y kind of guitar? Does the author really understand about the complicated relationships in bands?

And I’m happy to report that the answer to both of these questions is yes: while the kid’s band in this novel is probably not one I’d want to listen to in real life, their passion for it feels very authentic — and so does their taste in guitars and amplifiers. (At least Link is speaking the language of my music friends and past bands, having a character yearning for a Gretsch; even a Gallien-Krueger bass amp makes an appearance.)

You can read other reviews if you want to know more about the plot — but I hope you won’t. (Or you can go over to Cory Doctorow’s review, where he calls this book “A deceptively quirky tale with rusty razors at its core,” and carefully avoids spoilers.)

And I won’t say anything at all about the story, because I hope you will experience it the way I did, without knowing what to expect, except that Kelly Link is definitely a writer who knows what she is doing, and that she cares a lot.

As for me, yes, I did love, love, love The Book of Love. It’s a book that will stay with me for a long time and I have already recommended it to a lot of my friends. I hope it’s the same for you too.

Notes and more info

Thank you NetGalley and Random House Publishing Group for sending this book for review consideration. All opinions are my own.

Looking for more info about Kelly Link? This interview with Helen Oyeyemi feels very relevant! Horror Stories Are Love Stories.