Maybe it’s just a short story time of year

I’m writing this during the strange in-between world of the holidays at the end of December, when days are short and nights are long (for us in the north), when most of us are eating too much sugar, and people joke that they’ve lost track of what day it is.

And for me at least this time of year is also pretty emotional and complicated, which makes it tough to concentrate, or get much writing done. But it’s also not a bad time for catching up on sleep, listening to music, reading books, watching old movies, and going for walks — which can all be good things on their own, and can all help with generating ideas too.

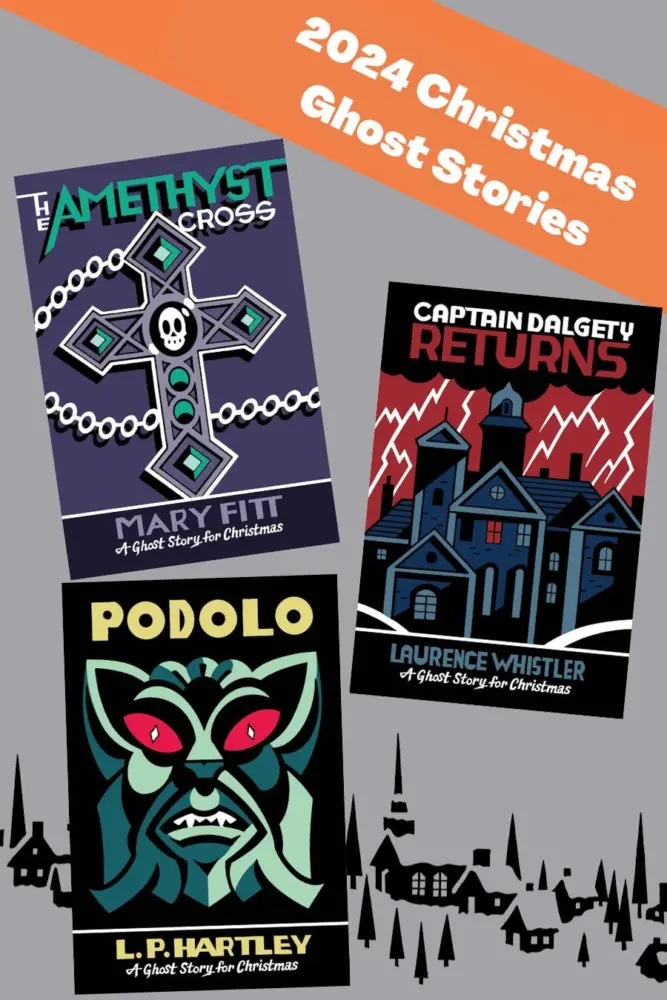

And I’ve also been thinking a lot about the Victorian tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas. Wouldn’t it be great to bring this back? I don’t think I’m the only one who wants it — thousands of us listen to CBC Radio’s annual broadcast of The Shepherd every year, and see for instance these little books illustrated by the great cartoonist Seth, and published by Biblioasis.

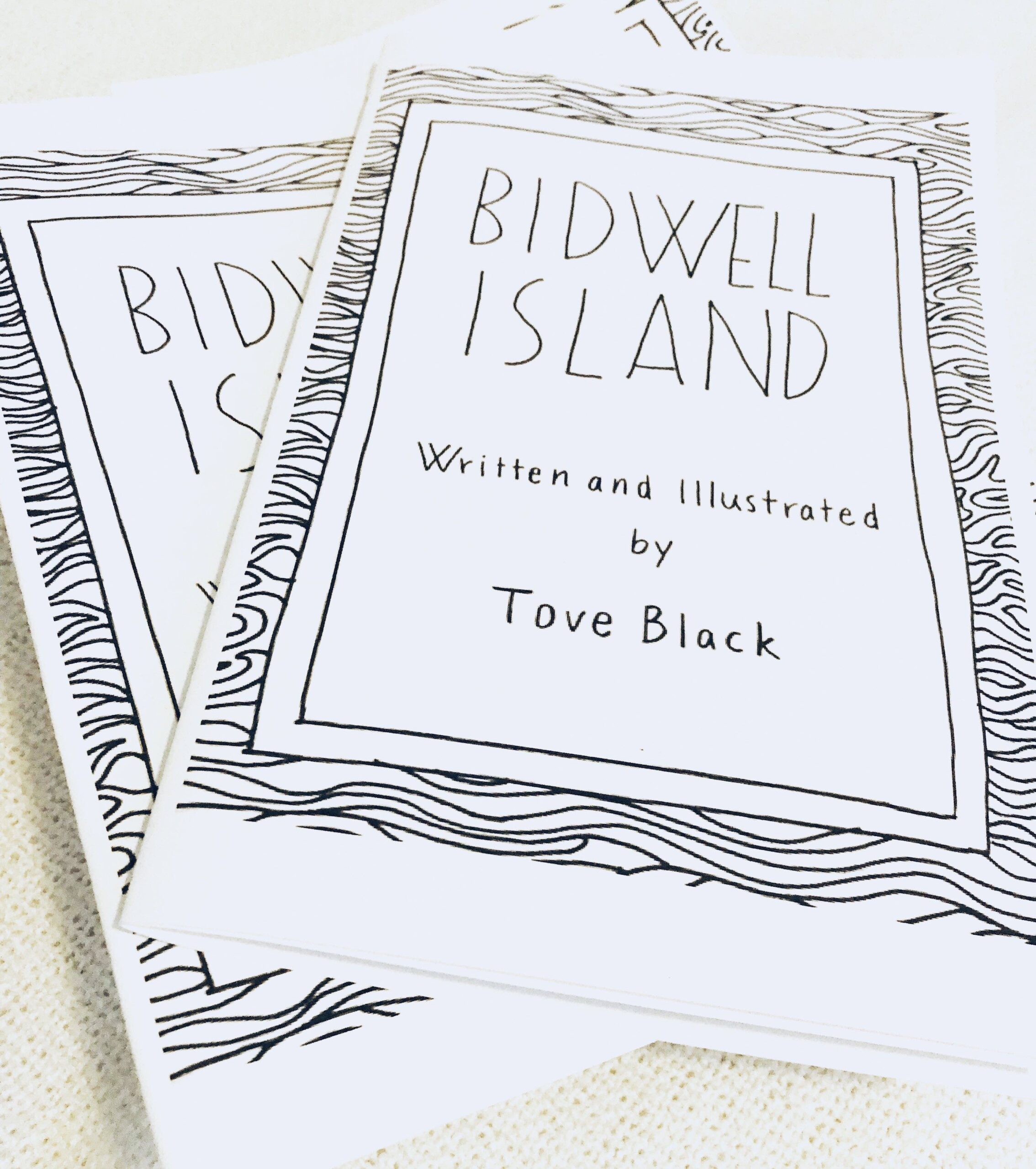

When I saw a display of these beautiful titles a few days ago at the counter of Upstart & Crow (a small and very elegant bookstore on Granville Island here in Vancouver) I took it as a sign — maybe it was time to go back to one of those strange little short stories I had sitting around, and make another zine.

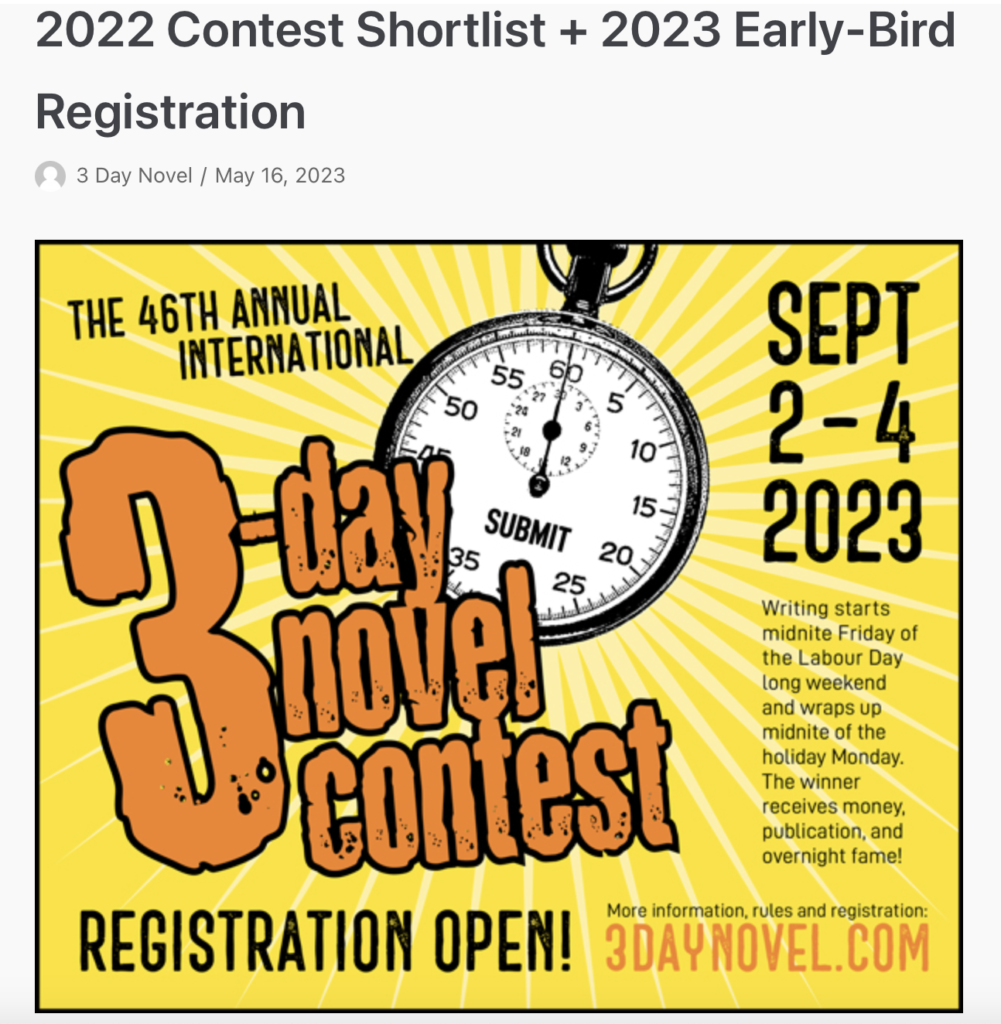

Because after a couple of years of being very focussed on novel writing, for the past few months I’ve been mostly working on short fiction — including some very short stories that started off as contest entries with strict word count limits. Mostly they’re what you’d call “literary,” but I have also ended up with a few little strange, oddball pieces, with elements of fantasy or at least weirdness. Not exactly ghost stories, but still… maybe I could do something with one of them?

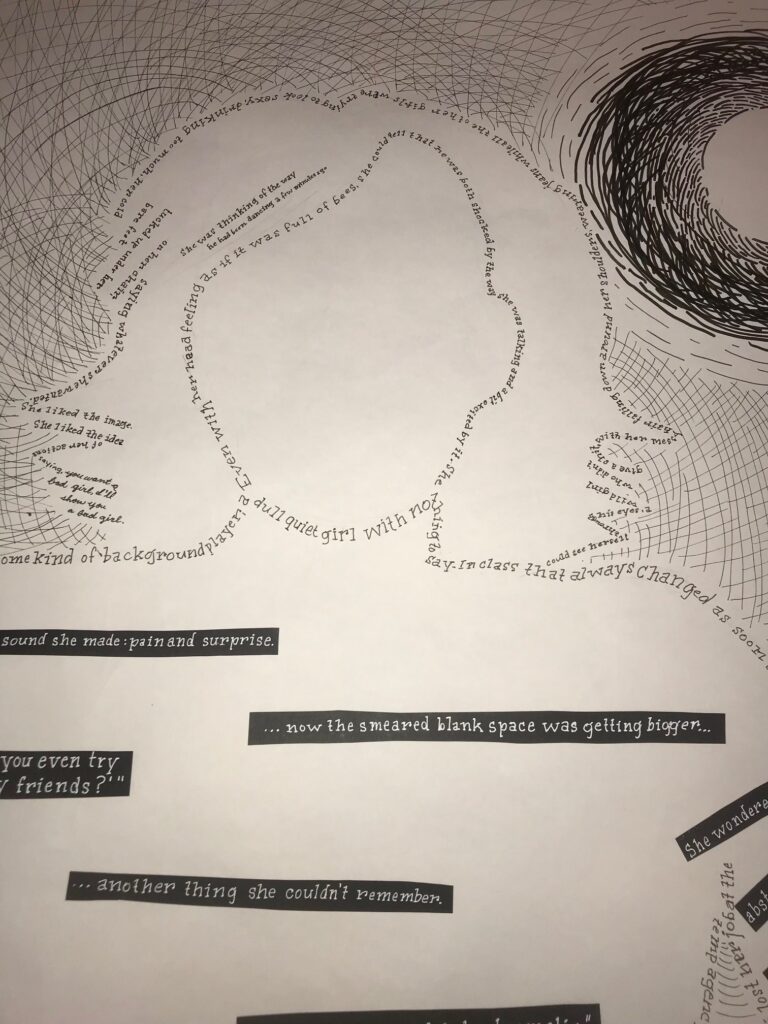

And let’s face it, it’s also satisfying to shift gears from just staring into screens and typing typing typing to drawing little pictures, laying out pages, and then taking a USB stick to my local print shop — and coming home with a stack of actual folded and stapled paper.

Giveaway

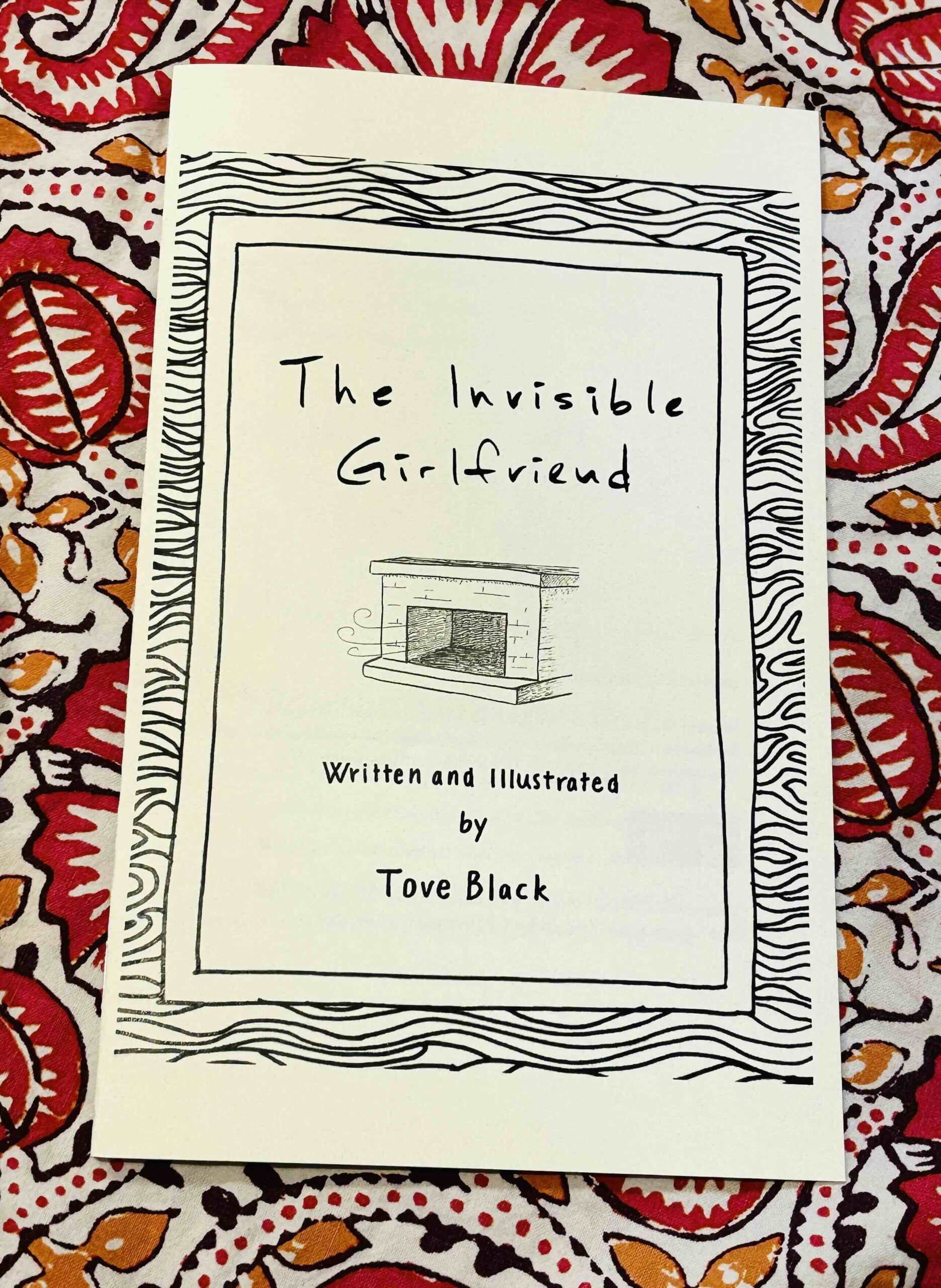

So here it is! “The Invisible Girlfriend” is a slightly weird and very short little story (under 500 words) that I originally wrote to enter a contest. (There is nothing like contests with challenging word-count requirements to generate ideas!) Later I added a couple of illustrations too.

Did I mention that it is very short?

And would you like a copy?

To enter your name in the draw, just message me with your email address via my contact form, and I will add you to my very informal and very home-made mail list. (I’ll only use this list to send out very occasional news updates — probably one or two a year.)

And I’ll randomly pull some names from my mail list in January, and contact the winners for details so I can send out physical copies.

Good luck!