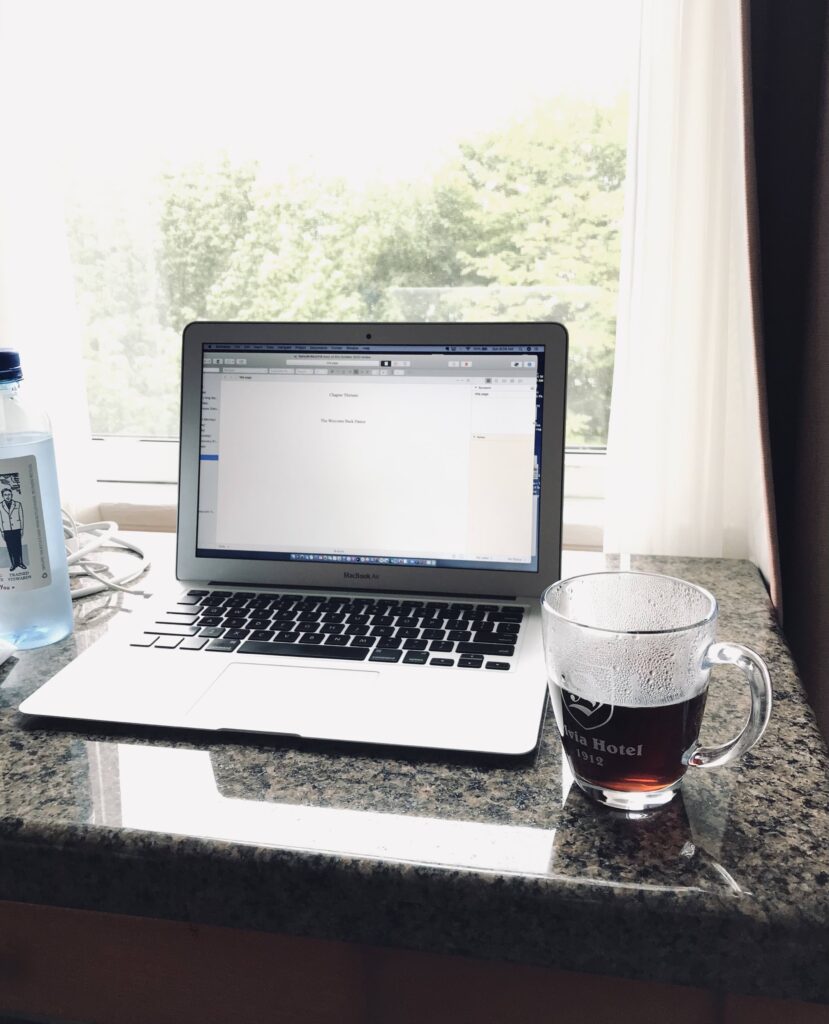

For about fourteen months, I’ve been writing for an hour* every weekday morning before work, and for a few hours every weekend.

Looking around at the friends I have who are lucky enough to still be working during this pandemic, I see folks adopting pets, hiking the local mountains, getting into shape, renovating their houses (or moving, or both), and perfecting or developing skills (including recording songs, baking, and making exquisite cocktails; one is even becoming a tie-dye master).

I haven’t accomplished anything that’s very visible.

Instead I’m escaping into an imaginary world from 7:30-8:30 every morning, and then dipping back into it here and there through the day, when I go for walks, do the dishes, drive somewhere, or just have a few minutes to think.

Unlike the chaotic real world — where the news is full of conflict, disease, hatred, and cruelty, and social media is puking up conspiracy theories and disinformation (alongside glimmers of the only connection most of us are getting with others these days) — the world of my own stories has patterns and threads that make sense — and if they don’t, I can reorder them, recreate them, even tear them out and throw them away.

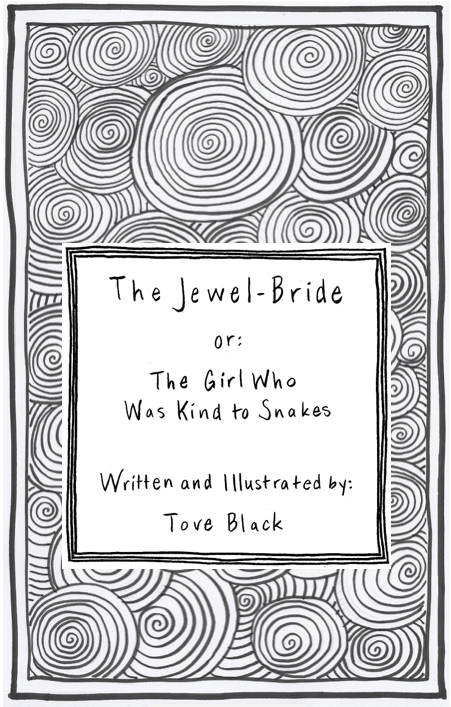

Although the two novels I’ve been revising and rewriting for this long pandemic year are quite dark, with themes of domestic abuse and dissociation, the world that I go to when I work on them is as lush and complex as any universe in any game. It’s also as strange and surprising as any dream.

And like a lucid dream, where you can switch on superpowers to fly away from a monster — and unlike real life — I can give my characters a way out. And in a novel, I’m learning this means building them long complicated escape routes, and watching the characters find their way.

Way back when I was a writing student at university, I remember instructors wrinkling their noses at the idea of “writing as therapy.” What they meant (what I think they meant) was that if you are writing something for someone to read, it’s about telling a story that works for the reader. On the other hand, when you are writing primarily for therapy — for instance, in a journal — then it’s only for yourself. So there are no rules: you don’t need to revise, or worry about structure, or story arcs.

And in the context of a writing program, one was clearly better than the other. So in my mind, for all these years, so-called “good” or “real” writing, and writing as healing, have been very separate.

When a writing friend and I signed on for this morning regime together, I thought it was an excellent and very practical idea, expecting that I would get work done as these writing hours accumulated. I also hoped that I would make big improvements to the mostly finished but very flawed manuscripts I already had — maybe even making them good enough to submit to publishers.

And that has happened! But over this past long year, it has surprised me — and given me great joy — to discover just how much the work part of writing, the unravelling and reweaving, the tearing down and rebuilding, the standing back to look at the overall shape of the story, has also helped me to live through these months.

———-

*According to my own rules, this hour of writing can include new writing, revising, or editing. A lot of is has been revising.

All photos by the author.

Update, July 2021

So many writers are saying this so much better than I ever could. Here’s just one of the quotes — this one from Rebecca Solnit — taken from Charlie Jane Ander’s forthcoming book, Never Say You Can’t Survive.

It’s due to come out next month and I’m really looking forward to reading it.