This novel I’m working on is set in a very specific time and place: Vancouver in late 1986, and partly in what we used to call the alternative music scene. My main character, Joni, joins a band, stays in a warehouse-turned art space, and goes to some “alternative” Vancouver clubs of the time.

However the way Joni and her friends think about alternative music is a bit different than the way people did in the age of Nirvana, Jane’s Addiction, and Lollapalooza — and after.

Is this important? (And is this something some of us spent way too many hours arguing about, decades ago?)

Probably not. (And definitely yes.)

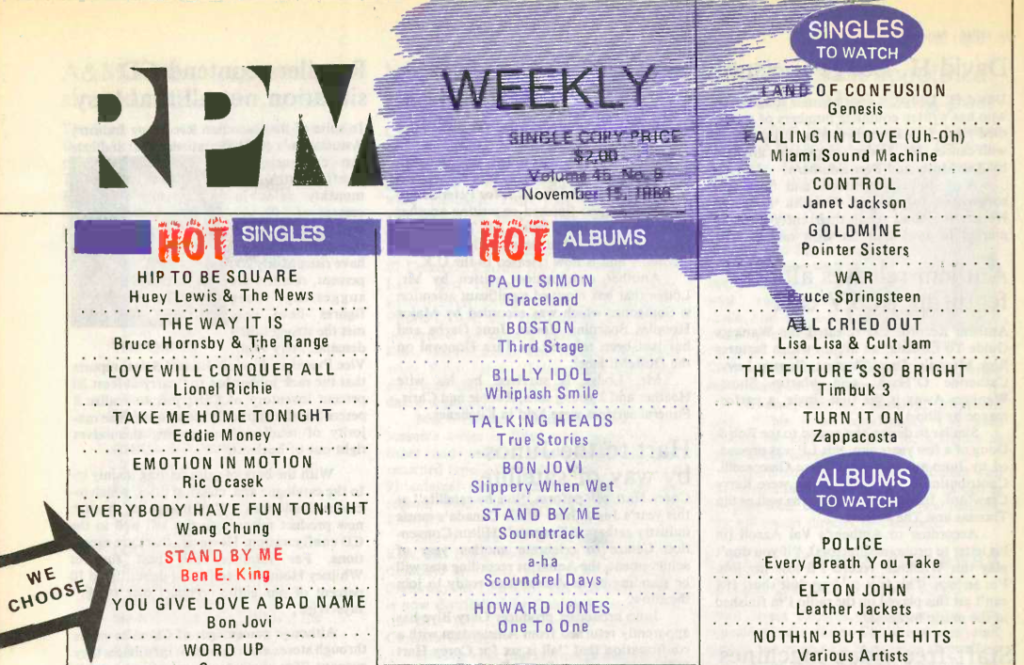

If you look at the best-known North American music industry trade magazines, and charts, you’ll see a certain kind of story about what was happening in music in the mid-1980s — but that was only one version of events.

There were also active and lively independent music scenes happening in different cities, with artists and bands performing live who only very rarely got radio airplay, and selling records (if they had records) in numbers that were too low to show up on sales charts.

But these independent artists were also attracting a large enough audience that — even in Vancouver — there were at least half a dozen venues where they could play.

Because radio, music videos (very expensive to make at the time), and most music news was so dominated by the major labels, campus and community radio provided an “alternative” — a way for listeners to hear something they expected to be more authentic and less processed, regardless of genre.

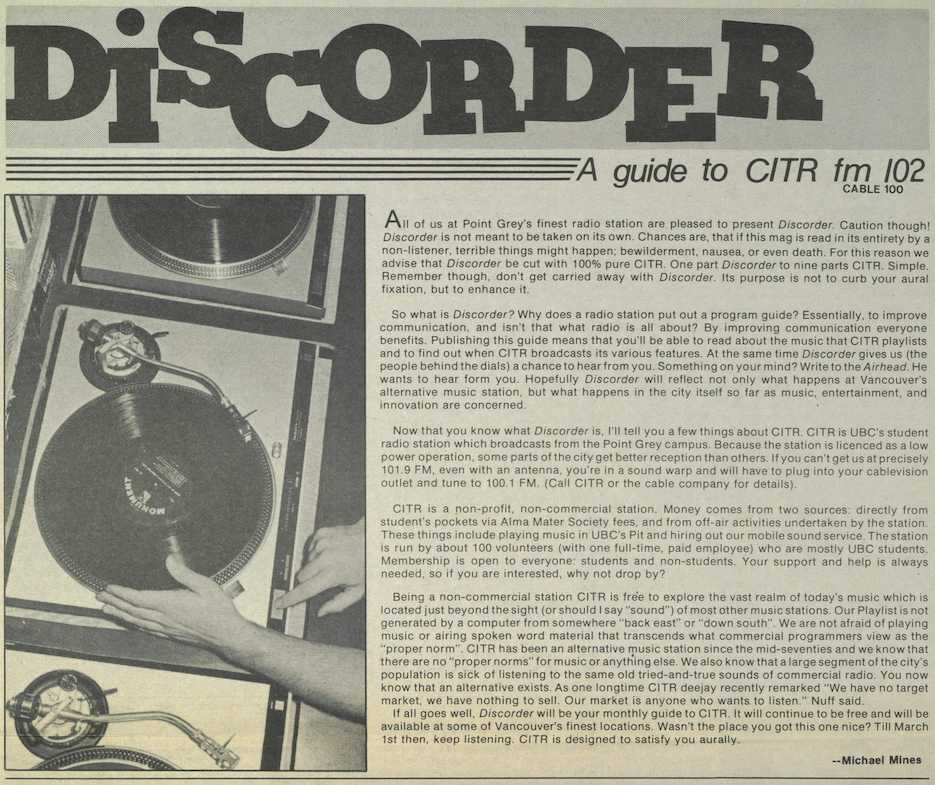

We…know that a large segment of the city’s population is sick of listening to the same old tried-and-true sounds of commercial radio. You now know that an alternative exists.

Michael Mines, Discorder, February 1983

By February 1983 the phrase “alternative music” was already well-established in the radio environment — at least in Canada — when the University of British Columbia’s campus radio station, CITR, launched their monthly magazine, Discorder.

As Michael Mines (then Discorder’s co-editor) puts it in the editorial that opens the first issue, “CITR has been an alternative music station since the mid-seventies…. We…know that a large segment of the city’s population is sick of listening to the same old tried-and-true sounds of commercial radio. You now know that an alternative exists. As one longtime CITR deejay recently remarked ‘We have no target market, we have nothing to sell.’”

And if there is no specific target market, and no need for a profit, that means the station’s playlist can be wide-ranging.* Looking through Discorder, you can see that “alternative music” (then and now) goes far beyond indie rock: the station has regular slots for folk, jazz, and reggae — and individual deejays play(ed) a much wider range of music than that on their own shows.

But even if campus radio had nothing they were literally selling, and refused to define what their product actually was (only saying what it wasn’t), they did have a product with a powerful appeal — because for listeners, the word “alternative” sounded subversive and full of possibilities. And a lot of us CITR listeners found out about the station the same way: someone breathlessly telling us about this wild radio station — run by students and (at the time) only available on cable or on-campus — who played what the commercial stations wouldn’t or couldn’t.

Campus radio was only part of it, of course. There were also national late night shows on CBC Radio that anyone could tune into if they didn’t have to get up early the next morning — Night Lines and Brave New Waves — and independent record stores that specialised in independent and imported music.

And of course there were those clubs. Because many of the bands playing live in the alternative scene didn’t have records or even demo tapes, the clubs were the only place to hear them. While the fictional Joni’s band is inspired by the Nuggets compilations and plays a type of psychedelic-tinged garage rock, she and her friends would have gone to the Railway, Savoy, Town Pump, Luv-A-Fair, and Arts Club and seen bands playing art rock, dance music, rockabilly, roots music, soul, even swing, among other genres — and many mixtures of these — as well as indie or alternative rock.

The JDs played swing and were also part of Vancouver’s alternative music scene.

*The term “alternative” as we now know it may even have originated from radio licences. It would take more time for me to dig into broadcasting licenses for the period, but in October 1984 RPM, a Canadian trade magazine, refers to “250 college and alternative radio stations across the U.S. and Canada.” (Source: RPM Weekly).

Notes and photo credit

As I write this (March 2021), we are still living in a pandemic. Nightclubs and theatres are closed here in Vancouver and in many places around the world, and most of us haven’t seen a live band in a year.

It’s an especially surreal time to be thinking about an age when this city had an active and busy live music scene.

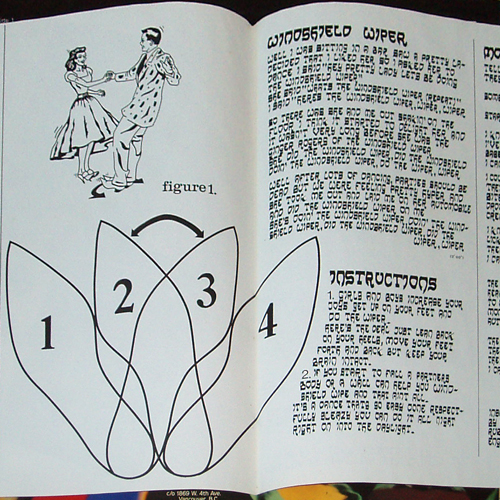

And that image at the top? It’s a diagram of The Enigmas’ Windshield Wiper dance, taken from the Strangely Wild EP. Photo credit: http://musicruinedmylife.blogspot.com/2011/11/enigmas-strangely-wild-1985.html